I’ve worked with a lot of startups - ones I’ve been directly involved in and others I’ve mentored or encountered at conferences in open spaces or after talks I’ve done. The first thing I pressure test with each of them is if the idea they’ve come up with is worth pursuing.

Three Criteria for Quick Pressure Testing of an Idea

The three questions your team should have a refined answer to are:

- What unmet need of an existing market are we satisfying? Startups rarely succeed when creating new markets, so instead you want a clear part of an existing market that has an unmet need you can satisfy.

- Who will pay for this system, and what are they used to paying? You need a clearly defined customer and an understanding of what they typically pay for services.

- Why are we uniquely positioned to succeed? Even if your idea is great if you don’t have a key reason for folks to pick you, they’ll pick someone else.

What unmet need are we satisfying?

It is far safer to create an alternate product in an existing market than to attempt to create a new market. It’s possible to succeed at the latter - usually when there’s a technology/market shift that creates a “land grab” opportunity (Like is happening right now in AI) but it is exceptionally risky and expensive. Instead, focus on a niche that is underserved in an existing space.

To define your market, be as specific as you can about:

- Who will get value from the product? The people who will benefit from what your product uniquely offers.

- Why do existing solutions not entirely satisfy them? The unmet need and what advantage does the user get from it being satisfied.

Your team has probably already defined a lot of this as part of their initial pitch, but double-check that they’ve hit all these points.

Is there a market?

When I’ve looked at product ideas, it’s always a warning sign if I can’t find two successful players already in the space. Consider the likely reasons that no one is serving the market you’re targeting: Either you’re the first to come up with this idea, or there’s a reason you haven’t figured out yet why the market isn’t there. Hint: it’s never the first one. For example, there might be hidden regulatory reasons or other barriers to adoption or cost that you’re not seeing.

Building out into a non-existent market is pure waste: You’ll burn your team’s time, your investor’s funds, and build a passion for something that will not reward you. Better to cut bait early.

Who will pay for the system and what will they pay?

To have an ongoing business, you need paying customers. This is the hardest part of any company: If you do everything else but no one will pay you enough for it, you’ve failed. If you can get people to keep paying you, you’ve succeeded.

Get Close to the Money

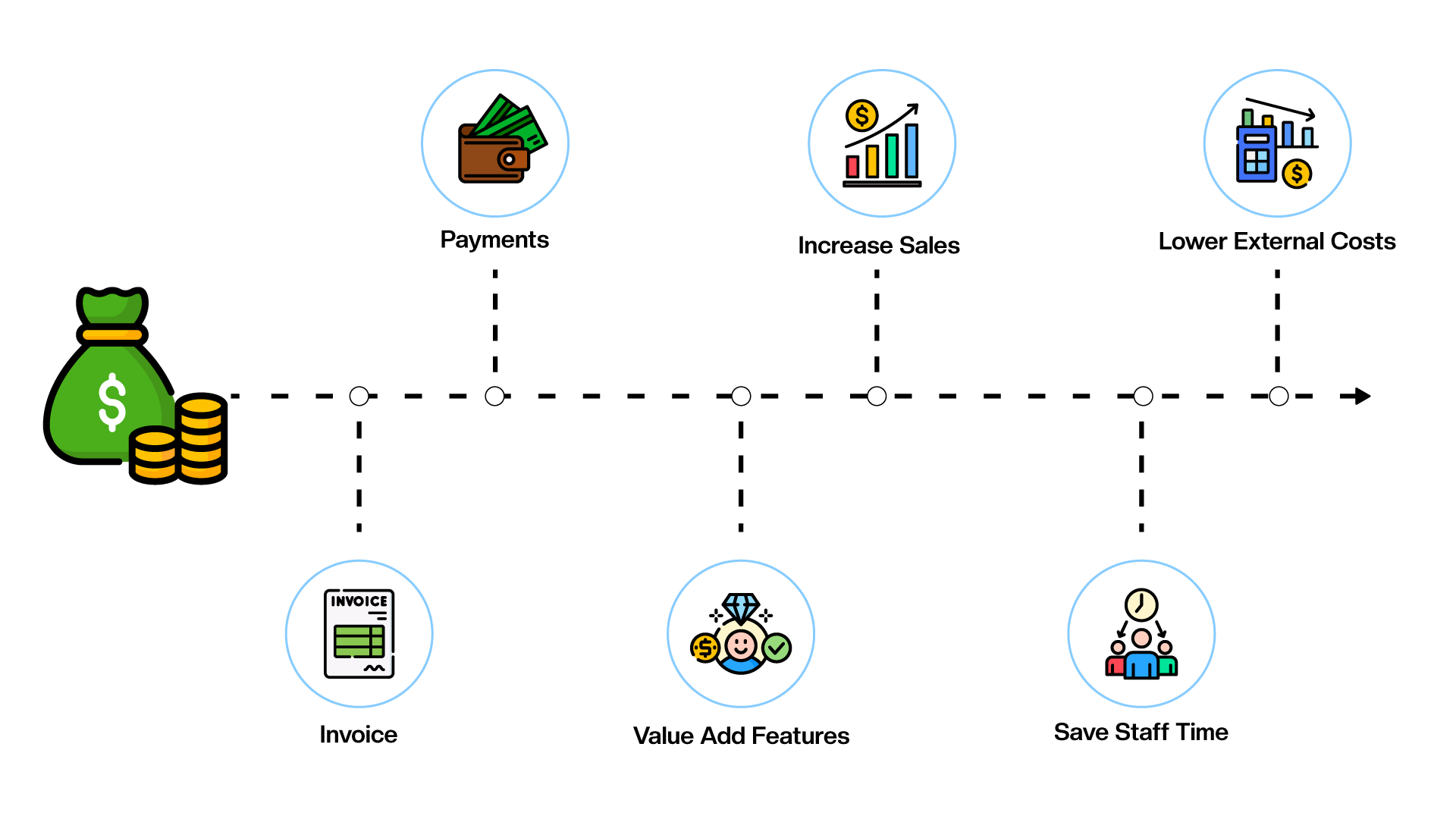

The shorter the path from your product’s benefits to your customer’s money, the easier it is to sell them on it. This is the journey your marketing and sales team is going to have to walk - anything you can do to simplify it will improve your time to revenue. In general, this means targeting users that are used to paying for products and services. After all, if they don’t have a budget or ability to buy your product then there isn’t a market there, even if they would willingly adopt it.

If your product is intended to generate value through cost savings - like reducing time, staffing requirements, etc - it’s often a much harder pitch than if it directly helps your customer create more revenue. Every business knows that cost savings are difficult to track and often don’t materialize. Even if adopting your product really will save a customer hours a week, unless they can put those hours to profitable use (or not have to pay staff for that time anyway) they won’t realize any savings.

The closer your costs can be associated with your customer’s revenue, the easier it is to get them to buy.

How Not to do it: Sell to Software Developers

My first startup where I picked the product idea was Gibraltar Software. We created Loupe, an embedded centralized logging & metrics system for Microsoft .NET. Overall I had good answers for many of these questions - I could see the unmet need in the market (particularly around deployed applications that weren’t always online) and had good reasons why we would succeed (in my career this would be the third time we took a hard swing at centralized logging and metrics so we had a deep understanding of the market, unmet needs, and a ready customer base to upgrade to it once we shipped).

It took a long time for Loupe to succeed because we underestimated the second point - who will pay for the system and what will they pay? When we started development, most developers used Visual Studio (which cost several hundred dollars per user per year) and there was a well-defined market of extensions and tools like profilers and specialized debuggers. But, that model was already on the way out as we were ramping up. Fast forward to now and all of the major development tools are free or nearly so. Some legacy tools can still charge (like Visual Studio, IntelliJ, etc.) but most of the players have been pushed out of the space.

As we talked with prospective customers, what was clear is that the folks that needed the product we made didn’t think they could get their company to buy something because, well, they never had before. In most cases, they wouldn’t even look at something that wasn’t free at least to start. Our value play was about cost and risk reduction - saving developers time. Even when they intuited the value of our product, they weren’t sure how to express that back to leadership in a way that would get it funded.

Fit with what they’re Used to Paying

As part of identifying the market your product fits into, you should identify the price points that customers are used to paying. You’ll need to fit into a band they are used to seeing. For example, most SaaS marketing apps have a price point of around $100/month for up to 5,000 tracked users. When you pick the price band you are going to use, you’re defining the battleground you have to win on: You need to make your product worth that price.

Your initial product has to be worth what the market expects to pay, not the other way around.

Why not go low?

If you’re thinking of going with a price well below the existing market, you are stacking the deck against yourself. First, people use price as a surrogate for quality - so if you’re cheaper, you’re doing less or they’re getting less. Second, it’s trivial for an established player to wipe you out of the market: they just need to come out with a cheaper option. At best, you’ll be committing yourself to take risks others in the market won’t so you can keep costs low - and operating at low margins where there’s not a lot of room for mistakes.

Finally, think about the kind of customers that will go with you because you’re the cheapest: These folks are placing cost above all else. That often means you may have collections problems with them, they are going to be resistant to upsells, and the feedback they will give you won’t be about creating more value but instead how to stay cheap.

Why are you uniquely going to succeed?

Even if you have a great answer to the other questions, if you don’t have a reason that your team is uniquely positioned to win customers, you probably should pursue another idea. The reason also has to be something about your organization, people, or brand - not that you’re good at developing or creating products. Why? Because competent execution is available to anyone with a bank account. If you’ve got everything else in place, you can always pay someone to execute for you.

A rough rule of thumb when creating a new product is that 20% of your cost will be in the engineering of the product itself. The rest goes into sales, marketing, and everything else it takes to get customers to adopt and pay for your product. So, even if you outsource development at three times the cost that isn’t as bad as it sounds, particularly since the main engineering costs come before the wave of marketing and sales costs.

Here’s why you can win

If you have an existing company and customer base, the best new product options are those that offer your existing customers more. The easiest way to do this is to look for other workflows your customers have that are adjacent to what they already use you for. This solves several problems in one go - you have an existing customer base to sell to that you already know will pay for a product, you already have a trusted relationship with them, and you can probably find ways to make the overall solution “better together” than others. This is the core reason that Microsoft, Apple, and Adobe can crush it with a new offering - as long as the customer sees that this fits with what they come to you for.

If you are a true startup - trying to launch a product into a space you don’t already have a foothold in1 - Then you need other reasons that people will buy from you. The key problem you’re trying to solve is finding your initial customers, getting them to buy the product, and getting them to recommend it to others. This usually is addressed through personal relationships your team has.

Let’s make a Dental Billing System

Let’s say your idea is to create a new billing system for dental practices. Perhaps you’ve worked out a way for small shops to get reimbursements from insurance much faster than they generally would. That’s nicely close to the money (if you can pull forward payments by 30 days that’s worth a lot to that business) but how do you get folks on board?

If your sister runs a large dental practice, your father is chair of the State Board of Dentistry, and you used to work for a major dental insurance company then you’ve got some solid reasons why you will succeed where others won’t - you can get some initial customers, find a platform to evangelize your solution at low cost, and you have a clear understanding of the true costs to deliver the solution.

Since I have none of those things, I wouldn’t take on that startup idea. Not because I don’t think I could do it, but because I don’t have a good reason why I would succeed in the face of a competitor that has the connections I don’t.

It’s not about the technology

In the example above, you’ll notice it doesn’t include any execution factors. You don’t want to lean into a reason such as you’d execute better, faster, cheaper, or using a particular technology. Those items can be achieved by any team that has funding and time. You need something hard for someone else to replicate so you have the space and time to create a product, bring it to market, and carve out a niche for yourself.

What if I can’t find a reason?

If you can’t work out why your team is uniquely positioned to succeed, you’ll need to expand your team. Just like you’d have to bring on folks to address specific technical challenges you may need to bring in people to address the “Why you” question. This is a major reason why so many startups are founded by sales, not execution, people - they already have a clear idea of how they can compete and win and a computer full of contacts to use to get there.

Finally, if you don’t have a satisfying answer to “why you”, the idea probably isn’t a good fit. That’s great news - you’ve eliminated an idea before you spent a pile of time & treasure on it. Don’t worry, another idea will be along soon.

Opt-Out Early

Product ideas should be treated like strong opinions, weakly held - While your team investigates them, you want to let folks go all in on the possibilities. Once the idea coalesces into something you might execute, it’s time to justify if it’s worth more investment. Most ideas aren’t - so we need to be able to let them go and move on to the next idea. Your team’s time is finite: You want to find the best idea you think you can execute, not the first idea that might be viable. The longer your team invests in the idea, the harder it is to let it go, so emphasize opting out early.

Discussions around product ideas must live in a “no-fault” culture: Your team is on one side, and the proposed idea is on the other. Think about how you communicate so you don’t end up with one person passionately defending the idea and others picking at them. It’s the idea that loses, not the individual or the team.

-

This applies to existing companies as well, provided that the new product is going into a market you are not already in. ↩