It was hard but worth it!

How many times have we all said that? It’s easy to assume that the more difficult something is, the more valuable it is. We’ve grown up with this message - the more challenging the work, the sweeter the reward. We’ve experienced it in our personal lives - exercising four times a week for months to lose weight, taking ever longer hikes so we can climb the trail up a mountain, skiing for years so we can safely fly down a double diamond trail.

And we’ve been teaching ourselves a lie.

People Value Outcomes, not Methods

Let’s say you want to hire someone to mow your lawn weekly. What do you value?

- The Lawn is mowed when the grass gets long enough: Depending on the weather, grass will grow faster or slower; you don’t care about it being mowed weekly; you want it mowed often enough that your lawn doesn’t look like it needs mowing.

- All the grass is cut: Regardless of the equipment used, you want to be sure it’s edged and trimmed so all the grass is the same height.

- Clippings are cleaned up: You want all of the grass clippings cleaned off your driveway and the sidewalk; if you’re bagging the clippings, you want the bags removed. In short - you want your property to look tidy.

For any vendor that can achieve that, there’s a price you’ll pay for their services - a reflection of the value you place on the outcome. You don’t really care whether they can do it with one person or five, in 15 minutes or 90. You might pay more for a higher quality of service or additional features, like weeding and fall cleanup, but the value you place on the core is constant regardless of how much work the vendor has to put in.

Now let’s turn it around and look at it from the perspective of the vendor: You could use a set of hand sheers, a push mower, or a large commercial mower. Your choice dramatically affects the effort that you’re putting into the job. But, the customer’s already determined the value1. So - regardless of the effort you put in, the value of the equation is already fixed.

Avoiding the Effort Trap

We use effort as a surrogate for value in decision making all of the time. For example:

- Sunk Cost Fallacy: We’re reluctant to discard a solution we’ve put a lot of time into.

- Endowment Effect: People tend to overvalue things they already possess or have invested effort into. This can make it challenging to objectively assess the true value of an asset or project.

- Overvaluing Perceived Hard Work: People may overvalue a solution simply because it requires a lot of effort to develop. They assume that because something was challenging to create, it must be more valuable, even if it doesn’t address the actual problem effectively or efficiently. This also applies to over-valuing employees who put in the hours independently of the results they’re generating.

Each of these is rooted in our intuitive, emotional thinking patterns we fall back on every day. To escape them, it’s essential to maintain a clear and objective perspective when evaluating the value of something relative to the effort invested. This includes regularly reassessing projects, considering opportunity costs, and being willing to pivot or abandon efforts when the expected value is no longer aligned with the effort required. Additionally, fostering a culture of evidence-based decision-making and open-mindedness can help individuals and organizations make more rational choices when it comes to resource allocation and effort management.

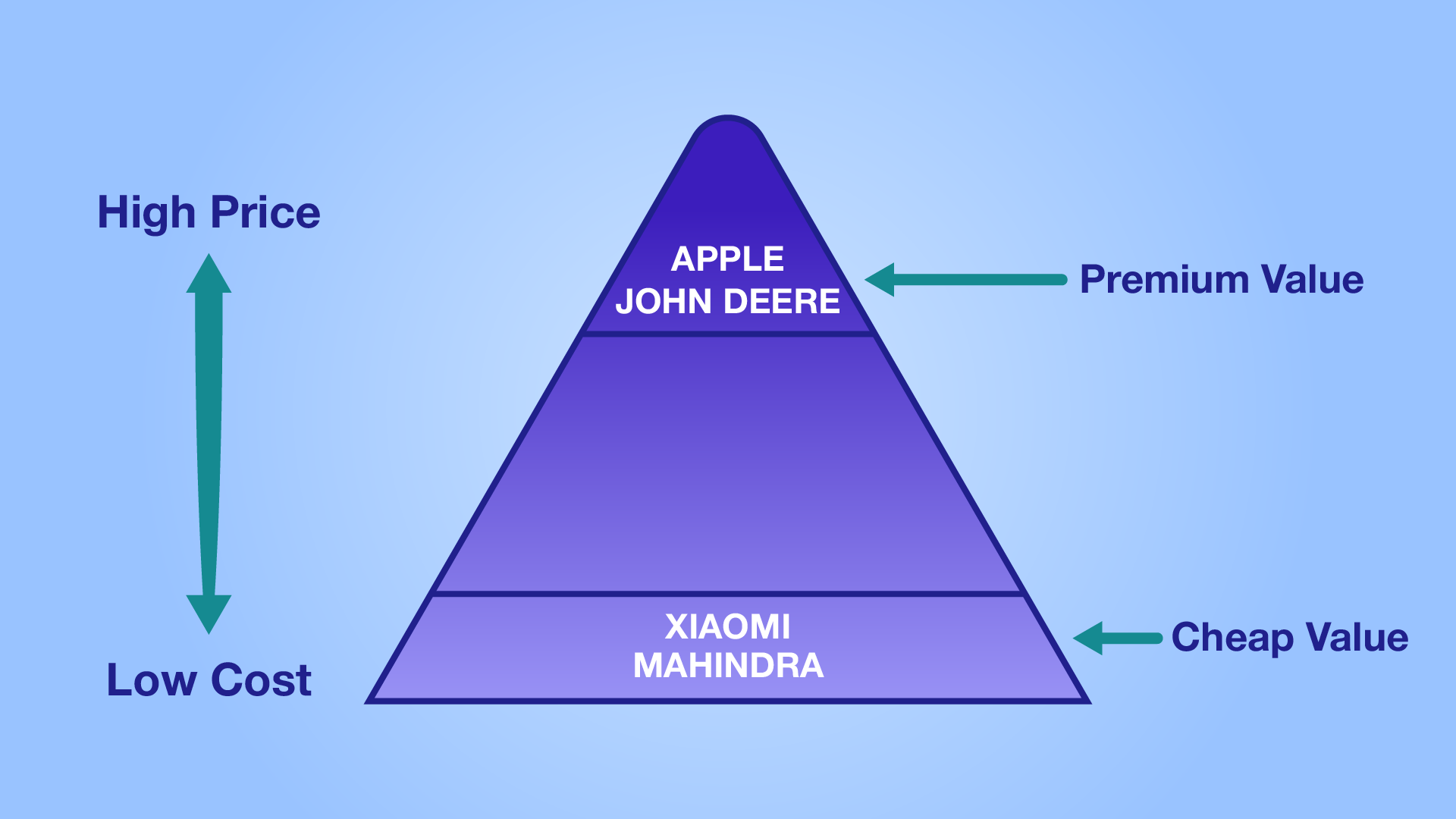

Value isn’t Cost Either

If you follow this train of logic to its conclusion, value isn’t directly scaled by cost either. Something cheap can be of poor value, and something expensive can be of great value. I was lucky to start my career with John Deere, a company with a long-term focus on building better products at the top of the market. Deere taught me that a product can be a better value than a competitive product even if it’s more expensive - as long as it exceeds the customer’s expectations. The core idea is to build a product great enough to justify its price.

The focus on Premium Value drives a virtuous circle that great brands understand - like Apple, John Deere, and Disney:

- If you believe you can charge more for your product because customers will value it more, you can invest more in the product.

- If you consistently exceed customers’ expectations at a higher price point than your competitors, your customers will have faith in your brand’s value when selecting a new product

- If your customers believe in your brand’s value, you know you can sell products at the top of the market.

This cycle works both ways - if you start by aiming at the Cheap Value market, you’ll have low margins and be known as the low-cost player. That limits what you can invest in your products, making it difficult to expand into new products or increase your margins. Your only path to revenue growth is volume.

There is a limit to value - for a given product, there’s just no rational value play above a certain point. This is the territory of luxury goods and luxury brands. If you’re in that space, you’ll have entirely different pricing considerations.

Aim for Premium Value

In any market there are three main value bands:

- Cheap Value: The product is a good value because it offers more for less money.

- Mainstream: The product is competitively priced in the typical range expected for the market.

- Premium Value: The product is a good value because it’s built to a higher standard. It costs more than is typical, but it delivers more.

Suppose you’re a small to medium player in your market (or a startup). In that case, I recommend creating products that focus on the Premium Value band: They are priced near the upper end of the competitive range but offer a compelling value proposition that justifies the price for their target audience. For startups, this can help make many product decisions before launch to ensure your initial offering justifies your asking price.

Targeting the Premium Value market may feel daunting - it raises the bar for your Minimum Viable Product (MVP) and can seem unobtainable. But let’s run through the alternatives:

- If you target Cheap Value, all someone else has to do is match your price, and they’ve nullified your advantage. The established players can easily do this - they’ve already made the significant investments to get to market and know their actual operation costs, you’re guessing.

- If you target the mainstream, you will have a challenge differentiating your product from the other mainstream products. Your sales team will want to lower prices to stimulate sales; before you know it, you’re a Cheap product.

- With Premium Value, you’ve got to offer a higher-spec product for at least part of the market.

The Premium Value playbook has a track record of success - niches are often small enough not to warrant the big player’s attention. Customers in nice markets will prioritize a narrow need and pay more for a product that satisfies it.

Learn More

- Crossing the Chasm by Geoffrey A. Moore - a classic book on understanding markets and how to find a successful niche in a large, competitive market.

-

This ignores luxury goods where the whole point is the extra effort put into the production of the item, like fresh hand-made food. Even then, do they care if you hand-sliced the lettuce or used a food processor, as long as it’s fresh? ↩